The first free Irish person will not be born, they will be formed in the national and class struggle that we as socialist-republicans have committed ourselves to.

We face ahead of us a seemingly insurmountable foe. The occupation of our island, the exploitation of the working people of Ireland, and the subjugation of our national destiny to the demands of the capital exporting bourgeois class appear to us as the guarding hound of Culann; an unbeatable enemy force standing between us and the future we wish to build.

However, the conditions we face in Ireland only appear unchangeable because we have not yet become the people who are capable of changing them.

In The Wretched of the Earth Fanon lays out the problem facing the colonised subject aspiring towards the liberation of their nation:

You do not turn any society, however primitive it may be, upsiude down with such a programme if you have not decided from the very beginning, that is to say from the actual formulation of that programme, to overcome any obstacles that you will come across in so doing

Frantz Fanon, Wretched of the Earth

Fanon here addresses the colonised subject who has recognised both the myriad impediments thrust upon their nation and its working people by colonialism and the need to act, and to act decisively. No amount of reform could address the underlying raw violence that sits at the heart of a colonised society.

Only through resolving to sweep away all of the mechanisms by which the nation and its people are subjugated can the colonised subject begin the process of decolonisation. Only by accepting that decolonisation must be achieved by any means necessary will the decolonial program be successful.

Where do we see these mechanisms in the colonised nation? They are ever-present.

While the most noticeable symbols of the subjugation of the Irish nation and its working people – the colonial and comprador police forces, the foreign government institutions and military installations, the private landowners who work in the interests of the capital-exporting bourgeois class – are the most visible and easily identifiable aspects of colonialism in Ireland, they aren’t the only areas in which colonialism has manifested. In fact, these targets of our program, being the most powerful, will likely be the last remnants of the colonial system to be dismantled in our nation.

The less easily noticeable way, but by no means less violent, in which colonialism manifests itself in Ireland is in our culture, or rather the suppression and commercialisation of it.

Cultural commercialisation

Whether in the free-state or the occupied six counties, the culture of our nation is subordinated to anglophone culture. Irish language spaces are exceedingly rare, and those that do exist only do so due to the diligent work of passionate volunteers and campaigners; even the Gaeltacht, the zone in which Irish is supposed to be the protected and primary language of public life, is treated as little more than a theme-park for tourists to visit for two weeks of the year.

Under the Stormont administration the Irish language service provision is ghettoised, restricted to a handful of communities, perpetuating the colonial myth that a person’s community background determines their ownership of their own national culture.

The situation for Gaelic Games is similar. In the south, the vast majority are hidden behind a paywall, restricting coverage of our national sports to a privileged few who can afford to pay for a streaming service, if the games have any coverage at all.

In the north, the level of broadcast coverage is even worse, and sports facilities are underfunded and neglected in favour of funding for grounds dedicated to British garrison games. Casement park, the largest facility for Gaelic Games in Ulster, has remained unusable for over a decade.

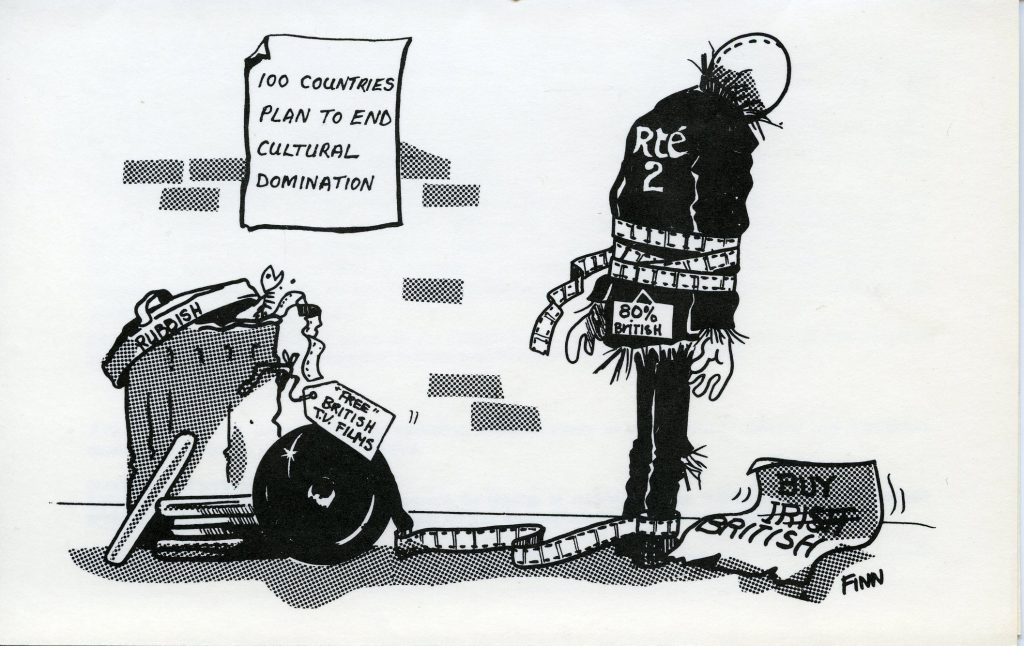

Our broadcast media is increasingly dominated by anglophone culture, with British and American media being seen as the norm rather than a foreign import. Those domestically produced pieces of media too are predominantly in English and are more-often-than-not retellings of British and American cultural tropes rather than an authentic representation of Irish culture.

Our culture is the culture of the subjugated, even in the ostensibly independent south. Our nation’s culture is rarely experienced by its people, and on the rare occasion when our culture is finally given a space to be seen and heard, it is in a format where a person would have to pay a premium to access it.

If it weren’t for the handful of community associations making Irish culture accessible for free, Irishness would be the domain of rich hobbyists, a dead culture only accessible for a high cost of admission.

Our national culture is the most basic aspect of our identity, the stifling of which stifles the Irish national ambition by denying the working people of Ireland an opportunity to imagine our nation free from the strangling influences of capitalist imperialism.

Before we can begin to overcome the baying hounds of occupation and wage slavery, we have to first overcome the influence of imperialist hegemony in ourselves. While we are unable to imagine a truly Irish future, we cannot plan the task ahead of us.

If we are denied the knowledge of our destination how can we possibly begin to plan our route? Our first task has to be liberating ourselves personally from Anglophone cultural hegemony – developing national consciousness.

Once we have understood the first front in the decolonial struggle, we must, as Fanon rightly observes, resolve to overcome this impediment to our national destiny by any means necessary.

What means are available to us?

What can the Irish nationalist in the modern age do to confront a globalised Anglophone cultural-media behemoth?

What is to be done?

It can, and necessarily should, start small.

We don’t begin our struggle by storming the barricades, we begin our struggle by understanding in ourselves why the barricades must be stormed.

Our first struggle is on the level of the personal; to begin to normalise and truly love and favour our national culture above the culture of the hegemon will be the first challenge we face as we take up our national cause.

What can we do in practice to begin this process? We can take up the cause of our national language; Take the time to study if you haven’t already begun doing so, use whatever Irish you have publicly and without embarrassment. To speak Irish in our nation dominated by the English language is a revolutionary act.

To hear others speaking Irish is a call to action.

Every foghlaimeoir and gaeilgeoir has had conversations with well-meaning people who say “I wish I had more Irish” or “I wish I had been taught Irish better at school”.

It is true that the system for teaching the Irish language is in dire need of overhaul, but far too many people who say that they wish they had a better command of the Irish language do not use the free time they have to build their fluency.

Far too many who say “I wasn’t taught Irish well” use that as an excuse for the rest of their lives not to pursue an understanding of their own national language. Many people truly do not have the time or energy after selling their labour for a pittance to make the effort to study, but many more do and instead squander that time on consuming Anglophone culture and endorsing the gradual erosion of our common culture.

To hear Irish being spoken around you, however briefly, however broken, is a call to speak what you have as well. A nation of béarlachas speakers is of more value to our national project than a handful of fluent gaeilgeoirí.

We can take up our national sports; We can attend the games of our parish and county teams. We can take our hurleys to public parks for a poc about. We can begin to learn how to play hurling, gaelic, handball or rounders if we have never had the opportunity before.

To attend these matches and play these games publicly is a revolutionary act. It is a rejection of the Anglophone hegemony that prioritises British garrison games and increasingly imported American past-times over our own national sports. To see people playing these sports is a call to action, to take up these sports for the first time or to return to playing, to watch your local team play or choose to watch it on television.

Many fans of the GAA will have had the experience of talking to well-meaning people who lament that it would be good if these sports got better coverage, that they would take the time to watch if there was.

It is true that coverage and grassroots financial support for Gaelic sport is in a poor state, and that radical improvement is necessary north and south, but while it is true that many people in our country truly haven’t had the opportunity to watch or play Irish sports, it is also true that many more choose to watch the English Premier League and spend their free time playing soccer or rugby rather than engaging with their own national culture.

The act of publicly showing your love for your national culture encourages others to do so. Our national culture is too valuable to leave to the state or sporting bodies to support on our behalf.

We can engage with and produce indigenous Irish media; We can read classic revalist stories, watch Irish language dramas and plays, attend trad sessions and learn to play Irish music.

To engage with these cultural forms, to appreciate and produce them, is a revolutionary act. In so doing you turn away, however briefly, from the predominant hegemonic culture and take time to enjoy and cultivate your own culture.

To commit to these acts publicly; to play music at a trad session, to perform as Gaeilge in an amateur dramatics play, to perform live readings of revivalist poetry, all these are revolutionary calls to action. Even if among those who see these performances only one person feels compelled to explore this media themselves, that is one additional person who has begun to value their own culture above the culture of the imperialist and occupier.

As with each of the previous examples of activity we can undertake, this act takes away some of the power the hegemonic culture has over you. It is an act that develops national consciousness in yourself and, in embracing these forms, you begin to cultivate a preferential love for your own national culture. In short, these acts are the first steps in standing upright as a gael – fully confident in your ownership of your own national culture.

These calls to action may appear individualistic; more concerned with the politics of personal consumption than they are concerned with the liberation of the nation and the masses that labour here.

However, without fully class and nationally conscious cadres, the socialist-republican movement will have no direction.

Only a cadre with a well developed sense of both class and national consciousness can bring about the liberation of our class and nation, and it is only through developing a favouritism for our subjugated national culture over the hegemonic Anglophone culture that is imposed upon us that we will develop a full national consciousness.

A decolonised Ireland will not result from speaking Irish, playing hurling or reading Ó Cadhain, but only movement stewarded by well-developed, proud gaels has a chance of striking the blow that is necessary to free Ireland and its working people.

National consciousness can only be developed within ourselves when we turn away from Anglo-American cultural forms and rediscover our own national culture. A revolution against the colonialist and imperialist exploitation of our nation led by proletarians who are well-read theoretically, but have no consciousness of national conditions, will inevitably fail.

No “New Ireland” can be built until an understanding is achieved by those who have resolved to build it of what ‘Ireland’ truly is; of what Irish culture is.

Any New Ireland Movement has to be committed to a national popularisation of a modernist, progressive Gaelicism. A New Ireland Movement that does not wholeheartedly adopt and promote Gaelicism is not a decolonial movement at all, as it has no commitment to a decolonial Irish culture, only a reassertion of Anglo-American culture.

A New Ireland Movement that does not wholeheartedly advance the cause of a modernist, progressive Gaelicism is not a decolonial movement at all, as it is contented to allow Irish culture to ossify and decay, like a museum piece to be observed in an Anglo-American cultural terrain.

These deviations from true decolonial Gaelicism will be the pitfalls of a movement whose cadre are not sufficiently nationally conscious, and this consciousness can only be achieved through a personal commitment to turn away from Anglo-American culture and a sincere re-adoption of Irish culture.

The task ahead

The Ireland we wish to build is one in which its workers have been exalted to command, its culture has been exalted to the dominant position, its destiny to be defined by the will of the nationally conscious working class.

To create this Ireland, we must first destroy the forces that stifle our ambition: the occupation of six north-eastern counties of Ulster, the power of the domestic and international capital-exporting bourgeoisie, and the hegemonic dominance of Anglophone culture.

These forces, like the hound of Culann, stand between us and our national destiny. They seem completely insurmountable. We must remind ourselves, however, that before we have taken up the struggle we are as Setanta was before he had committed himself to vanquishing the hound.

It is only when we commit ourselves, wholeheartedly, to our class and national struggle; when we take the first steps, however small, to the liberation of ourselves, our class and our nation from bondage, that we will fulfill our role as he did and become our own Cú Chulainn, the person capable of carrying out the tasks before us.

Bobby Sands, quoting an unnamed older comrade, said “everyone, republican or otherwise, has their part to play”. We do not have a choice over what our role will be. Our class and the place we call home has predetermined it. Our only choice is whether to shoulder this task or to shirk the responsibility placed on us.

To take up the mantle and responsibilities of the Gael, or to abandon our cause and allow the exploitation and occupation of our nation to continue.

The task ahead may appear impossible, but that is only because the person who will complete it will be born from us in our ongoing struggle.

An-mhaith ar fad. Is deas an rud ardán a bheith tabhartha don ghaelainn i gcomhthéacs sóisialach.