MR, Baile Átha Cliath

In 1983 the Eighth Amendment to the Constitution of Ireland was introduced, outlawing abortion in all circumstances except where the life of the mother was a risk, and also outlawing the provision of information on abortion. However, contrary to the stated aims of campaigners in favour, these restrictions did not result in fewer abortions taking place. Instead women were compelled to travel abroad to access abortion care, many going to the UK where abortion was available in limited circumstances through the Abortion Act 1967, (this did not include the 6 counties, where abortion was only decriminalised in October 2019 [1]).

In what seems to have been a step towards women’s liberation, on 25 May 2018, a substantial majority of the electorate voted to repeal the 8th Amendment, leaving the government free to bring forward a general scheme to regulate termination of pregnancy services in July 2018. The Bill was passed into law by the end of December 2018, allowing for the commencement of the Health (Regulation of Termination of Pregnancy) Act 2018 on 1 January 2019. For the first time in the history of the southern state, medical abortion up to 12 weeks’ gestation was permitted under medical supervision or later in certain restricted circumstances. Following the introduction of this legislation, an annual report into the ToP Act showed that a total of 6,666 abortions were carried out in 2019 and 6,577 in 2020.

While the introduction of this Act may lead to complacency regarding the fight for women’s reproductive rights, there still exist significant barriers to this form of women’s healthcare in Ireland. For instance, there is evidence to suggest that there are still substantial problems regarding the accessibility of information on abortion in Ireland; The Abortion Access Research Group conducted a study on individuals’ experiences of abortion provision in Ireland since the introduction of the Termination of Pregnancy (ToP) Act 2018. Over half of respondents (54%) did not know where to go to get an abortion, 32% reported they did not know where to find information on abortion, and only 65% of respondents were aware that abortion is free at the point when they sought to access care.

In addition to lack of information, there remains an undeniable barrier within both the legal framework of the Act and its operation which prevents access to abortion care. In 2019, 375 Irish residents were forced to travel abroad to access abortion care. Most of these individuals were seeking care during the second semester, with 20 percent of those experiencing fatal foetal anomalies. These statistics demonstrate that for many pregnant people, the ToP Act has not provided the necessary access to services. Abortion is one of the most common medical procedures in the United States, and in 2020, 209,917 residents of England and Wales received an abortion, which is an age-standardisation rate of 18.2 per 1,000 women aged 15-44. These statistics imply that access to abortion in other similarly developed countries is much more widespread. Although there is a similar demand for abortion care in Ireland, as demonstrated by the number of women who accessed abortion care in the state since 2019 and the numbers who traveled abroad prior to the referendum, access to facilities is much more restricted, a clear demonstration that people seeking abortions are being let down in this country. There are several factors contributing to the lack of access including cost, lack of service providers, a mandatory three day waiting period, and restriction of abortion after 12 weeks.

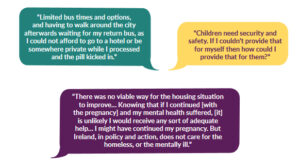

Only 1 in 10 GPs provide abortion services in Ireland and only just over half of maternity hospitals provide abortion services. This represents a significant barrier to accessing abortion, particularly for people in rural areas and from marginalised backgrounds who may face sizeable travel costs if there is no access to a provider within their local area. This also reflects a persistent mentality of shame towards women who access abortion procedures. Research from the Abortion Rights Campaign (ARC) showed that almost one in five respondents were refused care and refused a referral to another doctor, and some noted “these GPs were often rude and unsympathetic. Being refused care caused ‘fear’ and ‘confusion’ for participants. Some noted calling other GPs before finally deciding to import pills instead of continuing to pursue an appointment”.

Abortion services in Ireland are free at the point of delivery, but with some stipulations: you must be resident in Ireland and possess a PPS number, which not every person requiring an abortion has. This particularly restricts individuals wishing to access abortion care who are seeking asylum or living in Direct Provision. In this, as in many other scenarios, some of the most vulnerable people in Irish society are not being considered or cared for under the current legislation.

Under the current legislation, abortions after 12 weeks are tightly regulated and may only take place in a situation where two medical practitioners are of the opinion that there is a risk to life or of serious harm to the health of the pregnant person and it is appropriate to carry out the termination of pregnancy in order to avert the risk. Abortion is also permitted in instances where two medical practitioners are of the opinion (formed in good faith) that there is present a condition affecting the foetus that is likely to lead to the death of the foetus either before, or within 28 days of birth. These guidelines are the only way an abortion could be accessed for anyone who was unable to do so within the 12 weeks, and the guidelines do not take into account individuals who may be victims of sexual violence, minors, people living in coercive relationships, migrants or those living in Direct Provision, people who have recently experienced a crisis such as bereavement, or those who were unable to access a GP provider locally.

Despite the World Health Organisation’s recognition of abortion as essential healthcare, doctors who provide abortion after 12 weeks outside of the specific circumstances outlinds above may face a prison sentence of up to 14 years.

In their research on the topic, Donnelly & Murray (2019) argue that this law sets abortion care apart from other forms of healthcare and implies that doctors providing abortion care are in some way “inherently less conscientious than other professionals and that the usual regulatory mechanisms of (general) criminal and civil sanctions and professional/fitness to practice oversight are insufficient for these professionals.’’

They argue that as a result ‘’the Irish law perpetuates the stigmatisation of both the care provider and the recipient of abortion care.” Doctors interviewed as part of their research reported a “chilling effect” of criminalisation in their practice with one doctor commenting:

“In no other area of my practice could I go to prison for filling out a form incorrectly”.

In addition to the 12 week limit, there is a mandatory 3 day waiting period before an individual can access an abortion. The 2021 ARC report showed that many people suffered negative impacts of the 3 day waiting period, one person saying that the 3 day wait felt like “a punishment”, while others reported that it caused “undue stress and anxiety”. The World Health Organisation has stated that:

“Mandatory waiting periods can have the effect of delaying care, which can jeopardise women’s ability to access safe, legal abortion services and demean women as competent decision-makers”.

Currently there is an ongoing public consultation regarding a review of the legislation. The National Women’s Council of Ireland have outlined what should be campaigned for in this review:

- Review the 12-week limit and extend it into the second trimester: Abortion care, like all aspects of health care, should be decided in the context of a trusting and supportive doctor-patient relationship, whereby medical needs are met in line with clinical best practice and patient preferences.

- Remove the obligatory 3-day wait: There is no medical purpose or value to the three-day waiting period. This restriction impedes doctors’ abilities to provide urgent care when required while also placing additional stress on women.

- Remove the 28-day limit: All women with a diagnosis of severe or fatal foetal anomaly should be guaranteed compassionate care in their own country.

- Recognise abortion as a central aspect of healthcare and end the criminalisation of doctors: Abortion is recognised as an essential aspect of healthcare by the World Health Organisation. The criminalisation of healthcare in Ireland undermines doctor’s clinical judgement and professional expertise.

- Broaden coverage: Access to nationwide coverage of abortion services in primary care and maternity hospitals settings must be prioritised by the HSE.

- Introduce Safe Access Zones: Ensure that all those receiving and providing abortion care are protected from harassment and abuse.

- Contraception and Relationships and Sexuality Education (RSE): To realise the reproductive and sexual health rights of all, universal access to contraception and the development of a modern RSE curriculum must be addressed.

- An independent, external review of the legislation: Ireland’s abortion legislation is currently being reviewed. We want to see an external review that is independent, women-centred, transparent and inclusive.

Denial of access to abortion services has the potential to jeopardise a person’s physical and mental health and denies them autonomy, dignity and freedom. The denial of abortion access is a form of violence and oppression, and reflects a patriarchal agenda concerned with the control of the sexuality and bodies of women and pregnant people. It is crucial that we stand with women and pregnant people and ensure that they are given the reproductive rights and care that they deserve.

References

[1] Ryan, M., Nolan, A., & Vallières, F. (2022). Lifting the cloak of secrecy: Experiences of providing crisis pregnancy counselling in a changing legislative context in Ireland. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 22(1), 22-31.

[2] National Women’s Council (2021) ‘Accessing Abortion in Ireland’ https://www.nwci.ie/images/uploads/15572_NWC_Abortion_Paper_WEB.pdf

[3] Department of Health and Social Care UK (2020) National Statistics: Abortion statistics for England and Wales: 2020. Updates 4 January 2022.

[4] Department of Health and Social Care UK (2020) National Statistics: Abortion statistics for England and Wales: 2020. Updates 4 January 2022.

[5] Health Services Executive, “Hospitals providing abortion services” https://www2.hse.ie/ conditions/abortion/how-to-get-an-abortion/hospitals-providing-services.

[6] Abortion Rights Campaign and Lorraine Grimes. Too Many Barriers: Experiences of Abortion in Ireland after Repeal. Sept. 2021.

[7] Alliance for Choice (2020) ‘Up to 12 weeks access in Ireland’. https://www.alliance4choice.com/up-to-12-weeks-access-inireland

[8] National Women’s Council (2021) ‘Accessing Abortion in Ireland’ https://www.nwci.ie/images/uploads/15572_NWC_Abortion_Paper_WEB.pdf

[9] Abortion Rights Campaign and Lorraine Grimes. Too Many Barriers: Experiences of Abortion in Ireland after Repeal. Sept. 2021.

Other Works

Donnelly, M. and Murray, C. (2019) “Abortion care in Ireland: Developing legal and ethical frameworks for conscientious provision”. Ethical and Legal issues in Reproductive Health. November 2019, https://sci-hub.se/10.1002/ijgo.13025

Sheldon, S. (2016). How can a state control swallowing? The home use of abortion pills in Ireland. Reproductive Health Matters, 24(48), 90– 101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rhm.2016.10.002

Excellent article. Highlights issues which many people mistakenly had thought were resolved when the referendum was passed.