CM, Béal Feirste

It is the sad fact that in Ireland we have had multiple Bloody Sundays. The most infamous two being the 1921 massacre in Croke Park, and the 1972 massacre in Derry carried out by the Parachute Regiment, which we are yet to see justice for. However, Ireland’s first Bloody Sunday of the 20th century happened on this day in 1913, carried out by the quislings of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) and the Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP).

Between January and August 1913 there had been roughly 30 strikes in Dublin alone. The Irish Transport & General Workers Union (ITGWU) was experiencing a growth in membership, and needless to say, the capitalist class of Dublin were not fond of this new growth in working-class organising. The Dublin working-class was some of the most exploited and rundown in the whole of Western Europe at that point. 28,000 people lived in tenements deemed entirely unfit for human habitation by the standards of Dublin Corporation; coincidentally 13 members of Dublin Corporation owned such tenements. In a study conducted in November 1913 it was revealed that the 5,322 tenements in Dublin housed 87,305 people, with 20,108 entire families living in single room apartments. [1] With these conditions in mind, the growth of the ITGWU should come as no surprise.

On 26 August 1913, the Dublin Lockout commenced. It would prove to be a decisive moment in Irish labour history, but ultimately a defeat. The Lockout began when 200 tram workers belonging to the ITGWU went on strike for union recognition. In the weeks leading up to 26 August, hundreds of tramline workers suspected of being ITGWU members had been fired. Working conditions on the Dublin tramlines, owned by William Martin Murphy, included 17 hour work days and an extensive system of fines and punishments for the slightest infraction. Ultimately, the strike on 26 August failed, with strikebreakers being used to ensure the trams continued running as normal.

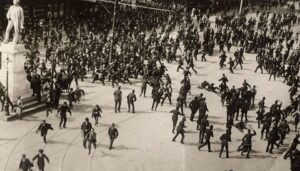

Over the next few days, continued attempts were made to stop the trams, and skirmishes between trade unionists and police continued – many of the latter having been transported in from across Ireland to deal with the strike. The conflict exploded on 31 August. James Larkin had been banned from speaking in Dublin, as his presence was deemed to be incendiary, but nonetheless he was snuck into the Imperial Hotel where he made a brief appearance before being arrested. The polic reaction was described in an interview years later by one of the women involved in the subterfuge, Helena Moloney: “Well the police then got savage, they were very angry at being circumvented like that, and they advanced on the crowd and batoned right and left”. Passers-by returning from church, curious onlookers, trade unionists alike were batoned in the frenzy of violence. Indeed, most of those attacked were not involved in the strike at all, as many ITGWU members were at another meeting in Croydon Park at the time.

Up to 600 people were injured in the charge, the night prior to Bloody Sunday the police had also mortally wounded two men, John Byrne and James Nolan, whose deaths are occasionally misattributed to the events of 31 August. Robert Monteith described one of the attacks,

“One of the Constabulary walked from the centre of the road on to the sidewalk and, without the slightest provocation, felled the poor man with a blow from his staff. The horrible crunching sound of the blow was clearly audible fifty yards away. This drunken scoundrel was ably seconded by two of the Metropolitan Police, who, as the unfortunate man attempted to rise, beat him about the head until his skull was smashed in several places. They then rejoined their patrol, leaving him in his blood.” [2]

It was this grotesque violence against the workers of Dublin that directly led to the formation of the Irish Citizen Army, an organisation committed to the defence of working-class interests and to achieving a socialist republic.

What is the significance of “Labour’s Bloody Sunday” for us today though? Ultimately, it is a lesson in the nature of the state, and the role of police. Both police forces in Ireland have carried on the tradition of their RIC ancestors. It may be tempting to simply point at the actions of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), and the infamous pictures that made their way around the world as they batoned civil rights protestors in October 1968, and to continue with “historical” examples. The reality is that just as the RIC and DMP of 1913 sought to protect the interests of capitalists – and British imperialism – their present-day counterparts do the exact same thing. In February 2021 police in Belfast arrested a survivor of the 1992 Sean Graham Bookmakers shooting for attending a memorial, citing Covid-19 restrictions. By comparison, weeks before, the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) was given a comfortable fifteen-month deadline to stop its racketeering. In September 2018 masked Gardaí aided unidentified, balaclava-clad thugs in carrying out a forced eviction of a squat in Frederick Street, Dublin. More recently, in April 2021 the Gardaí dragged protestors away from a picket outside a Debenhams in Dublin.

It should always be remembered where their loyalties lie and what their interests are. No amount of public relations campaigns or community engagement days will change the fact that when push comes to shove, as an institution the police exist to protect the status quo and the interests of the ruling-class.

Jose Maria Sison summarised that states are “the special instrument of class coercion over another class in order to realize a certain kind of society”. [3] Bourgeois societies have enshrined the dominance of the bourgeoisie over the proletariat by means of anti-trade union legislation, the banning of organisations and parties, and laws which place greater protection on empty private property than on tackling extortionate rents. Police are the means by which these laws are enforced. It is important that the socialists of today learn the bloody lesson of 1913, and take it to heart: uniformed lackeys of the elite are not our friends.

Sources:

[1] R. M. Fox, History of the Irish Citizen Army (1943), pp 18-21.

[2] As cited in R. M. Fox, History of the Irish Citizen Army (1943), pp 6-7.

[3] Jose Maria Sison, Marxism-Leninism: A Primer (1982), p. 46.