CG, Baile Átha Cliath

Hwang Dong-hyuk’s Squid Game is the newest in a growing library of South Korean anti-capitalist media that has made waves in the West, following on from the likes of Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite and Snowpiercer (as well as the identically titled Netflix adaption of the latter). Set in modern South Korea, where people under severe debt are approached by a mysterious organisation and coerced into a survival game, the main protagonist, Seong Gi‑hun, owes millions of South Korean won to both banks and loan sharks. His debt and a deteriorating relationship with his daughter all culminate in him approaching a mysterious organisation, who offer billions of won as a reward for playing “games”. These games are brutal blood sports, usually ruthless adaptations of children’s games.

A provocative and deep criticism of South Korean capitalism, Squid Game offers several stark observations on the depredations of the system. Capitalism has forced working-class people like Gi-hun into such dire material conditions that blood-sport is seen as a lesser evil. In episode two, the players vote to leave the island on which the games are played and return to South Korea. However, after returning home, Gi-hun finds his mother near-fatally ill, but unable to afford to leave work to stay in hospital, instead taking her chances. After this, Gi-Hun, alongside many of those who had previously left the island, decide to willingly return. These people would rather take their chances in a system where they could die any day, at any time, rather than return to South Korea where they are subjected to debt, poverty, alienation and other capitalist miseries. This raises the issue of freedom of choice under capitalism. Its supporters like to say that capitalism is rooted in freedom of choice as, unlike slaves, workers are not owned and forced to work for a capitalist, but are rather free to seek out the employer of their choice. However, this fails to acknowledge the fact that, as workers must work if they wish to buy food, pay rent, pay medical bills etc., they are beholden to a relatively small group of employers for their means of subsistence. Working-class people must subject themselves to capitalist exploitation in order to survive. This same logic is applied to Squid Game: yes, the players have voluntarily (re)joined the game, but their circumstances have led them to see no viable alternative. Squid Game draws a clear comparison between so-called “voluntary” participation in capitalism and the blood games.

Our subject also demonstrates how the material conditions of society mould the types of people in that system, an idea stemming from the Marxism concept of base and superstructure. For example, as the games progress, our protagonists become more and more desensitised to violence and its effects, and become more willing to ignore any cultural stigmas surrounding its use. While playing the marble game, Gi-hun and Sang-woo both manipulate their opponents to win, resulting in the deaths of two other players. Characters like Gi-hun have been shaped by the material pressures on the island, where ruthlessly winning games ensures survival and wealth. Similarly, under capitalism, the most ruthless and emotionless capitalists will generate the largest wealth. Capitalism makes capitalists and aspiring capitalists completely abandon their morals if they wish to succeed. Likewise, only the most brutal and emotionless competitors will survive the games. As the game progresses, most of the players forget about the money and simply wish to survive, leading them to do terrible things. This is contrasted to the start of the show, where Gi-Hun steals money from his own mother to place bets, to accumulate more money, but with the goal of paying his debts so he can give his daughter a good birthday. Many workers, when faced with imminent poverty and debt will be forced to turn to less desirable methods to survive, including crime. Squid Game shows that capitalism draws the worst out of people, forcing them to compete in a competition of ruthless profit accumulation, directly similar to the competition on the island.

This logic of survival and ruthlessness inevitably leads to certain groups of people being discriminated against within the capitalist microcosm of the games. The dominant logic is that large, strong, and middle aged/young men should form groups for protection from others and in helping through the games. In the tug-of-war game, where a team of ten strong men will be the clear favourites, the women, elderly and disabled people are ostracised and subsequently killed off all the quicker. This is extremely reminiscent of capitalism, where a person’s worth is directly related to their ability to make profit for their capitalist overlords. Likewise, in Squid Game, your value to society is measured by how you can help the individual win the prize money and/or survive. Ali Abdul, a competitor missing two fingers Is implored by Sang-woo to hide his disability, otherwise the other men would be reluctant to join their tug-of-war team. Once the teams are decided, Sang-woo voices his displeasure at being stuck with three women and the elderly man, demonstrating the sexism and ableism that grows out of the economic necessity within the games’ system. It is difficult not to think about the Covid-19 pandemic in this context, as we have seen a heartless, individualistic mindset with regards to a willingness to allow the elderly and most vulnerable to die, rather than take steps which would impede upon capital.

Ali Abdul serves also as a representative of immigrant workers in South Korean society. We see that Ali is overly polite and almost grovelling to his South Korean peers, a sign that his life has been difficult. Like many immigrants in modern capitalism, he has to be a perfect representation of morals and politeness if he wants to maintain a good image and survive. Ali represents how migrant workers must grovel to survive in a system which weaponises racism and xenophobia, both in the games and in the global economic order. Han Mi-nyeo. a rather pathetic figure, uses the dirtiest possible tactics to survive, including racism. When she struggles to find a team which can help her survive she points to Ali who should not have a position of privilege over her as he is not Korean. The saddest aspect of Ali’s character is how his bowing down (literal and metaphorical) to Sang-Woo causes his death. He puts too much faith and trust in Sang-Woo, who tricks him into losing the marble games, resulting in Ali’s death.

Despite her detestable treatment of Ali, Han Mi-nyeo is also a victim within the games as she is a woman. As already noted, women are not given much of a chance within the blood games and so Mi-Nyeo weaponises one tool she has as a woman over the men; her sexuality. She attempts to flirt with and seduce the strongest men, or even just the men who will give her a chance to survive. This is allegorical for women in capitalism who are sometimes forced to use similar lines of work to survive. This also raises the question, is consent under economic coercion consent at all? How can Mi-nyeo give consent when she is faced with death? This same logic can be applied to capitalism, especially in the Global South where the sex trade is particularly coercive, due to the overwhelming influence of Western imperialism.

Imperialism and its effect forms a major aspect of Don-hyuk’s work. The VIPs, a group of foreign, male millionaires/billionaires are brought onto the island to watch the blood games while being given a lavish holiday experience. These men wear masks and so their identities are hidden, but they do appear to be mostly American and European. They seem to be the consumers of the crude entertainment made from these games, a possible analogy for the sexual imperialism we see today in places like Thailand, where rich Western men arrive for sex holidays. One particular VIP, an American, not only attempts to rape one of the workers on the island, the undercover Hwang Jun-ho, but is also enjoying the games in some perverse, sexual manner. There are clear allusions to Jeffrey Epstein’s island, through a group of rich, aristocratic men going to an island to receive illegal sexual gratification.

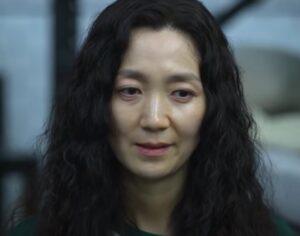

One can not mention imperialism in Korea without covering North Korea. Sae-Byeok is a player from the DPRK and she is representative of the dialectical relationship between capitalism, imperialism and North-South relations in Korea. We see that Sae-Byeok is dehumanised as a “commie bitch” for being from the DPRK, something we can infer is relatively common in South Korea. Sae-Byeok is used as a tool of irony to show how the hyper-capitalist dystopia of South Korea is justified through anti-communist and anti-DPRK propaganda. When another character asks Sae-Byeok if South Korea is better than the DPRK, Sae-Byeok does not reply. This question is so ironic as it is asked while both women are faced with imminent death as a direct result of South Korean capitalism. Furthermore, as Sae-Byeok dies, she states that she wants to return home, presumably referring to the DPRK. Squid Game is perhaps one of the most nuanced depictions of the DPRK we have in mainstream media and it is fair in its analysis of North-South relations, never taking a chauvinistic approach.

There is certainly much more one can talk about with regards to the show, including the role of the guards on the island who offer a solid commentary on capitalist police forces. Squid Game is a pertinent and relatively complex critique of capitalism. Director and creator Hwang-Dong hyuk brilliantly elucidates so many different elements of capitalism, from sexism, ableism, imperialism and propaganda, all while expertly balancing the national and international elements.